As a software developer, you’ll work on a variety of applications each with their own unique architecture. Or maybe you’ve inherited a brownfield legacy mess! You can make your life and other developers’ lives less painful by adopting some patterns and best practices.

When building an object-oriented system, in a language such as Microsoft.NET C#, you’ll want to make it easier to maintain and extend over time. This is especially true when working on enterprise systems that often contain hundreds of thousands of lines of code.

Throw in a few offshore development teams and suddenly enforcing company-wide development standards that adhere to best practice isn’t relegated to those in architectural ivory towers; it can become mandatory to help ensure the development factory is running efficiently.

In this article, we explore a set of principles called SOLID that can help alleviate some of these pain points and help remove code smells.

Download our SOLID Principles list to start improving the development of your software.

Origins

The SOLID mnemonic was introduced by Michael Feathers in around 2000 and stands for the 5 main concepts of object oriented coding and software design.

- Single responsibility

- Open-closed

- Liskov substitution

- Interface segregation

- Dependency inversion

The idea behind these principles is that when each is observed, the developer is more likely to create a system that is easier to maintain and extend. In the following sections, we’ll discuss each of these points in turn.

[bctt tweet=”Using #SOLID principles means a system that is easier to maintain and extend.” username=”GAPapps”]

Single Responsibility

This principle basically states that each class should have single responsibility for one area of functionality provided by the solution, and that all required code should be encapsulated by that class.

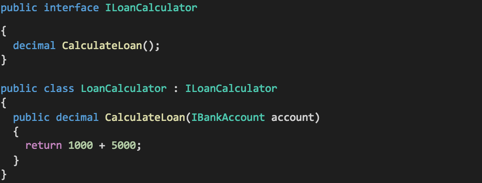

Take the example below. We have a loan calculator interface and a class that implements it. The class is responsible for only one thing, any new features or methods that get added to this interface or class must purely related to the “loans”.

Open Closed

The Open Closed principle states that:

“software entities, classes, methods, etc. should be open for extension but closed for modification”.

Modification to the entities behavior can be achieved by extending its features but not modifying its source code.

One way to adhere to this principle is by using inheritance as it allows you to take a class, inherit from it and extend the existing functionality where you need to.

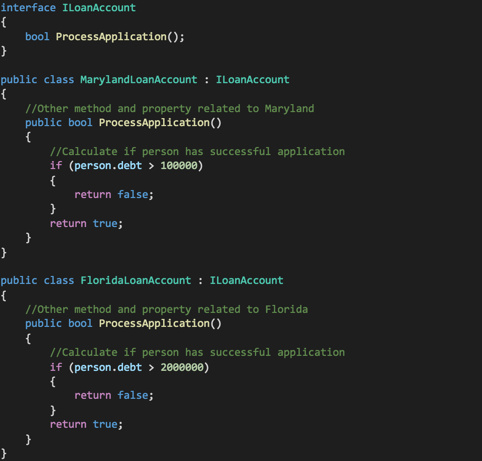

Imagine our Loan Calculator had to be used in a different bank or State, we may wish to keep some existing functionality but have different implementations of the ProcessApplication method which determines if a person has been accepted for a loan:

Liskov Substitution

This principle is named after Barbara Liskov who originally talked about the problem in 1998. She states that:

“you should be able to use any derived class in place of a parent class and have it behave in the same manner without modification “

It ensures that derived classes do not affect the behavior of the classes they are inheriting from. Or put another way, that any derived class can take the place of its parent class.

Here is a real-world example to bring this concept to life.

Perfect substitution

[table id=1 /]

If the parent glass is broken, it can be replaced with the child. A person can drink from each cup, and it belongs to a kitchen.

Violating substitution

[table id=2 /]

The images above show a violation of the principle. Water can be poured into both, but a person cannot drink from the watering can.

Download our SOLID Principles list to start improving the development of your software.

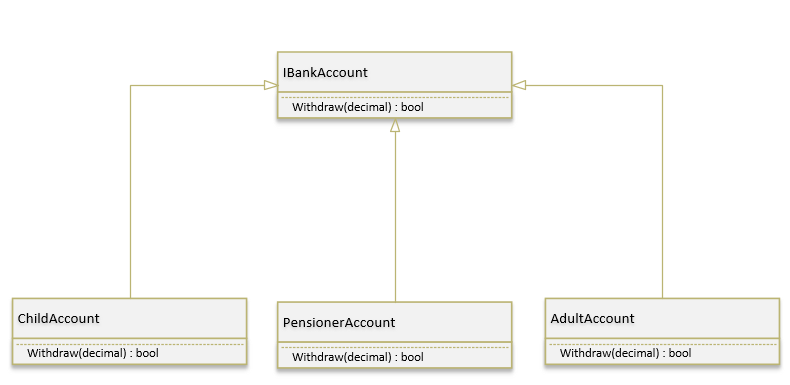

Consider the following class hierarchy where we have three types of bank account that implement an interface IBankAccount:

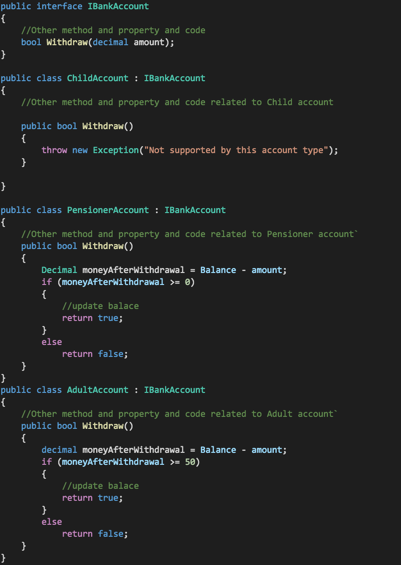

For completeness, the following code is present in each class:

As per imaginary business rules, the ChildAccount doesn’t allow any withdrawals for the time being whereas other account types (Pensioner and Adult) are allowed.

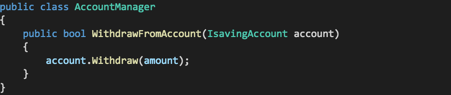

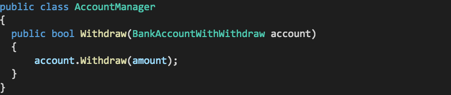

Consider the following method in our AccountManager class:

Which in turn invokes either of the following methods:

An exception is being thrown from the Child Account class, because of this, the Liskov Substitution principle is being violated.

Remember the principle states that functionality from the parent class should not be broken in child classes?

How can this be fixed?

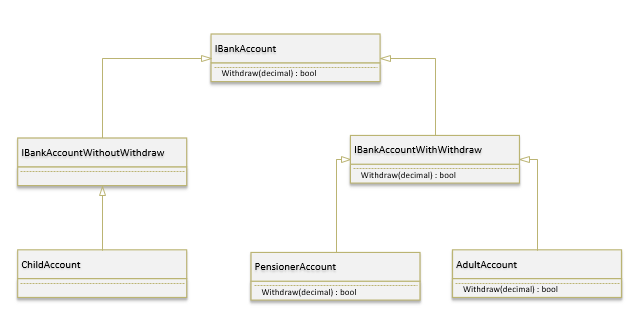

We need to verify the inheritance hierarchy isn’t broken as we create classes. In the following revised class diagram, two new classes have been added and the child classes inherit from the relevant parent class:

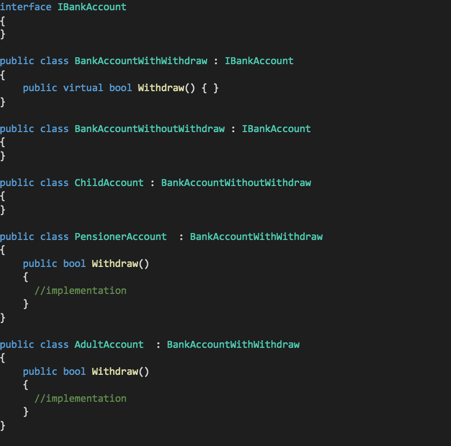

The code can now be written as follows:

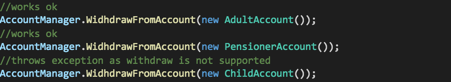

The AccountManager class can now be invoked via the following method. Note the “account type” must be of type BankAccountWithWithDraw.

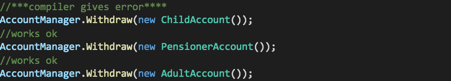

However, when trying to perform a withdraw against a child account, the compiler will notify the developer:

This is because the ChildAccount does not inherit from IBankAccountWithWithdraw.

You can see that by implementing this principle we prevent the possibility of runtime exceptions being introduced or business rules from potentially miscalculating values.

Interface Segregation

This principle states:

“that clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use”.

This principle is about breaking down monster interfaces into more specialized fine-grained ones.

Imagine there were 10 more methods in the ILoanAccount interface and we didn’t have direct access to the interface source code. We may not want to implement every single method either. Our only choice would be to implement the methods we’re interested in and ignore the methods that aren’t relevant to our class.

It’s not ideal but it would work.

[bctt tweet=”#SOLID #InterfaceSegregation: ‘clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they do not use'” username=”GAPapps”]

You could throw a NotImplementedException for guidance in terms of the methods we didn’t need to implement but the interface explicitly mandated.

If you’re a Microsoft.NET developer, you will be aware of the Membership Provider. This was great when integrated with SQL Server and gave you lots of user administration methods such as Change Password, DeleteUser etc.

But say you wanted to roll your own implementations of the Membership Provider. You were forced to implement almost 30 methods! You may not want to do that though, and only need to change one or two.

Dependency Inversion

This principle consists of two points:

- High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

This principle is about reducing the dependencies amongst classes in an application.

You can think of it as low-level objects providing coarse-grained interfaces that high-level objects can use, without the high-level objects having to know or care about the specific implementations provided by low-level objects.

Examples of this may be system auditing, notification mechanisms or database layers. Imagine our LoanCalculator had to perform an audit of each user interaction in the system, either to the file system or database.

A class called AuditManager resides in the business logic layer and is responsible for invoking the audit mechanism via the method LogMessage(string message). In most well-architected systems you’d have a business logic layer to house complex rules.

The LoanCalculator solution contains the following interface:

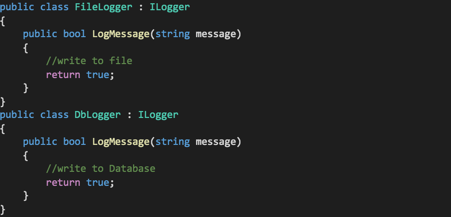

And the following concrete classes implement the ILogger interface:

Now here is where it gets interesting. We know that AuditManager needs to invoke LogMessage(“Customer Processed”) but we aren’t interested in the implementation of how it achieves this “under the hood”.

Prior to adopting SOLID principles, the AuditManager may have directly called something like .LogMessageToFile() or .LogMessageToDatabase().

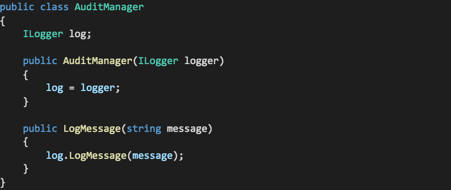

By adopting the dependency inversion principle, the AuditManager can be written like this:

So, what’s going on here?

The AuditManagers constructor accepts any class that implements the ILogger interface. This is called constructor injection.

Depending on the type being passed into the constructor (DBLogger or FileLogger in our case), the application will write audit records to the database or file system.

It means that whenever .LogMessage() is called by AuditManager, it doesn’t care how the low-level audit operation is being dealt with. It’s an only concern is to invoke LogMessage() and let the low level (concrete) logging classes deal with writing to the file system or database.

In an ASP.NET application, the config option could be controlled via the web.config file or a similar XML application settings file thereby meaning audit providers can be swapped in and out easily, (providing they adhere to ILogger interface).

Summary

In this article, we’ve run through the SOLID principles in turn and some examples. Whilst they aren’t a “silver bullet”, by implementing them you can ensure that your application’s codebase will be easier to maintain and support.

What’s been your experience with SOLID principles?